I was contacted by F8 Magazine (an online photo magazine from Spain) late in 2010; they had found my work on Photoshelter and had perused my online portfolio and liked what they saw. So, they sent me some interview questions and asked for some of my favorite images and they put together a great spread in their second issue, just released in mid-February. Following are the layout and interview, but to see it all as it was intended to be seen, see the online magazine.

Hi Chris. Tell us a little bit about yourself.

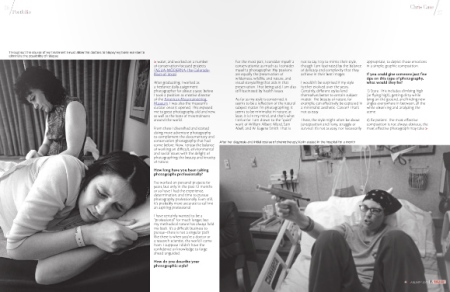

I was born in Connecticut and grew up along the New England coast. I received a degree in neuroscience and worked for a number of years as a researcher in that field, first with patients with schizophrenia and then, literally, slicing monkey brains in a study of Parkinson’s disease. It was in that basement laboratory, under fluorescent lights, slicing frozen monkey brains eight hours a day, that I decided to pursue photography. It was not a terribly difficult choice. Of course, it has been a bit more difficult to succeed as a photographer than it was to take that first step and apply to graduate school for photography.

What or who got you started in photography? Is there any formal training in your background?

I’m not entirely sure what my initial attachment to photography was. In college I was interested in art and photography, as a way to balance my life while studying neuroscience. I ended up with a second degree in art and art history, of which two photography classes were a requirement. The professor I had for that initial photography class would become a great mentor, friend, and influence on my work.

But, most important to my development as a visual storyteller, and the most influential and life-changing work I’ve been a part of came from one of my first “projects.” While I was still working in the neuroscience field, I was in a relationship with someone who was diagnosed with leukemia. I immediately started documenting her life, treatment, and recovery, and our life together. I had only known her for eight weeks, and we spent the next four years together. The camera became a part of both of our lives, as much a method for dealing with the circumstances as it was a tool for documenting our shared experience; I documented as many intimate moments as I could. See a gallery of images here. It wasn’t until later that I discovered Eugene Richards’ work “Exploding Into Life.”

Still, time spent slicing brains ultimately led me to seek a degree in the field. That’s how I ended up at the University of Texas at Austin for their master’s program in photojournalism. There, I became devoted to environmental issues, particularly water, and worked on a number of conservation-focused projects.

After graduating, I worked as a freelance daily assignment photographer for about a year, before I took a position as creative director of the American Mountaineering Museum. I was also the museum’s curator once it opened. This exposed me to great photography, old and new, as well as the feats of mountaineers around the world.

From there I diversified and started doing more adventure photography to complement the documentary and conservation photography that had come before. Now, I enjoy the balance of working on difficult, environmental and social issues with the delight of photographing the beauty and ferocity of nature.

How long have you been taking photographs professionally?

I’ve worked on personal projects for years, but only in the past 12 months or so have I had the experience, determination, and time to pursue photography professionally. Even still, it’s probably more accurate to call me an aspiring professional. I have certainly wanted to be a “professional” for much longer, but my methodical nature has always held me back. It’s a difficult business to pursue–there is not a singular path like there is when you’re a doctor or a research scientist, the world I came from. I suppose I didn’t have the confidence or knowledge to forge ahead unguided.

How do you describe your photographic style?

For the most part, I consider myself a conservationist as much as I consider myself a photographer. My passions are equally the preservation of wilderness, wildlife, and nature, and visual storytelling that aids in that preservation. That being said, I am also still fascinated by health issues.

As far as my style is concerned, it seems to be a reflection of the natural subject matter I’m photographing. It seems to be minimalist in nature; at least, it is in my mind, and that’s what I strive for. I am drawn to the “quiet” work of William Albert Allard, Sam Abell, and W. Eugene Smith. That is not to say I try to mimic their style, though I am fascinated by the balance of delicacy and complexity that they achieve in their best images.

I wouldn’t be surprised if my style further evolved over the years. Certainly, different styles lend themselves better to certain subject matter. The beauty of nature, for example, can effectively be captured in a minimalist aesthetic. Cancer? That’s not as easy. There, the style might often be about juxtaposition and irony, struggle or survival. It’s not as easy, nor necessarily appropriate, to depict those emotions in a simple, graphic composition.

If you could give someone just five tips on this type of photography, what would they be?

1) Stare. This includes climbing high (or flying high), getting dirty while lying on the ground, and finding new angles everywhere in between, all the while observing and analyzing the scene.

2) Be patient. The most effective composition is not always obvious; the most effective photograph may take you 100 attempts to get exactly what you want. Don’t settle for anything less.

3) Be intelligent and thoughtful and respectful. Know your subject before you begin photographing, then allow the subject to lead you to what you should be learning more about. Be open minded so that new observations are put to good use in framing the story, rather than ignored because of any preconceived notions of what the story “should” be that you might have started with.

4) Experiment. Forget what you learned and try a new approach. Perhaps that’s creating an abstract world from something familiar, or distilling something highly complex to a graphic essence.

5) Stare some more. Find something better, or different, or unique, and know that you’re the only one that is creating the work, and the audience’s reaction to it is often unpredictable. Don’t make photographs that you think people will like; make photographs you like.

You are the editor and director of photography and design of Trail & Timberline magazine, published by the Colorado Mountain Club since 1918. Tell us, what is the focus of the magazine and how does it expand your ability as a photographer?

Trail & Timberline is a reflection of the Colorado Mountain Club, so its focus is conservation, education, and recreation, specifically related to Colorado’s mountains and mountaineering. Ideally, there is a mixture of each of those things in every issue (see some samples here).

I am a staff of one: editor, photographer, writer, and designer. Besides being very rewarding, challenging, and fun, working on all parts of the magazine helps me to understand the packaging of photography and visual stories, which in turn makes me think about these things when I’m in the field. It makes me a better photographer, and a better journalist. Of course, there are certainly times when I’d like to be collaborating with a dynamic and creative staff; I’d like the pressure that would come with delivering for a photo editor. But, I have the challenge of balancing all of those roles simultaneously. It’s a very satisfying feeling when it all comes together.

What are the typical preparations that need to be made before a shoot? (Both in terms of camera equipment and researching the location itself / weather etc.)

Nothing beats spending time with your subject, whether that subject is a person or a place.

As far as equipment is concerned, I’m a minimalist. I carry three lenses most of the time; I never use a flash. I am often trying to capture nature, so I feel as if introducing unnatural light would be absurd. If my battery is charged, then I am ready to go.

As far as adventure photography is concerned, there are certain precautions that I take, particularly in the winter when there is the risk of avalanche. Checking the avalanche data regularly throughout the winter is just a habit now. Thankfully, in Colorado there is a great website for this.

Likewise, weather is a concern in slot canyons. If there is any chance of rain, it’s not a wise idea to be wandering around in a giant funnel of rock. Having patience and waiting for stable conditions is just a part of exploring that world.

Will you ever feel like your work is completed?

That is a very difficult question to answer. Certainly, there are times when I feel like nothing can change the environmental catastrophes that seem to be raging around us. There are times when I feel like all of my efforts to tell visual stories won’t change the overwhelming momentum that they’re up against.

So, I suppose my answer would be “no.” I don’t think my work will ever be completed because I don’t think there will be a time when conservation doesn’t need the help of story telling. In a more general sense, my work as a story teller won’t be finished because there will always be stories to tell.

I just hope that along the way I can contribute to the preservation of a particular landscape, or change the behavior of people, or excite and inspire someone through my work.

What’s the most inspiring location you’ve visited so far?

I seem to be fascinated by any new place I go, and tend to be inspired everywhere I go, whether that’s a delicate shortgrass prairie on the Great Plains, a lush estuary on the Gulf Coast of Texas, or the jagged drama of the Swiss Alps. That being said, I can’t remember ever being as awestruck as when I recently trekked the length of the Haute Route, from Chamonix, France, to Zermatt, Switzerland. It’s not the most remote area, or the least populated, but there’s no denying that it’s gorgeous (see images from the Haute Route).

But perhaps the most inspiring place I’ve been is southern Utah. It’s like no place else on Earth. I’ve been countless times to explore the canyons, formations, alcoves, ancient dwellings, mesas, and mountains, and I’ve never been disappointed (see images of Utah). It is always inspiring to be present among such a unique landscape, with a palpable feeling of quiet around any corner. The forms, the shapes, the experiences you can only have in a place where time is evident in every rock around you, and you are perceptibly small in a vast spread of geologic time. As may be evident, it helps me to think and makes me philosophical. And the scenery never ceases to amaze me, or inspire me.

Unfortunately, much of this iconic landscape remains unprotected. And the threats to it only increase with time. This is especially true of places like White Canyon. To think that places like this exist nowhere else on Earth, yet remain unprotected from vehicles, development, oil and gas extraction, is alarming. I couldn’t imagine a world without them in their pristine state. That’s why I work with organizations like the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance to help them educate people to the threats these iconic landscapes face.

What kind of impression do you hope to leave upon others who see your photographs?

I believe all I can hope to do is make people think. A photograph doesn’t bring about change by itself. A person has to use that photograph, or be used by that photograph, in order for action to take place. And the first action is always thought.